BioWire Weekly - 022

Biotech News

Happy Monday Evening, Readers. Let’s be relentless this week!

Before we get into biotech news, I have a few quick housekeeping items.

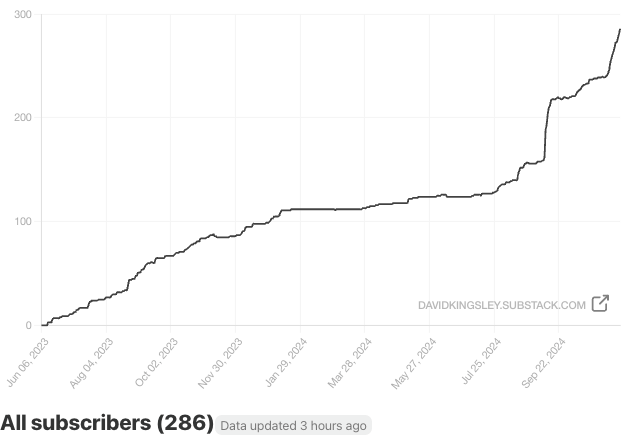

First, it seems like we've been growing quite a bit lately, and I want to extend a warm welcome to our new readers! I also want to thank everyone who has helped grow and support Neural NeXus. This has truly been a fun and rewarding journey, and I never expected so many readers would tune into our Stack.

For those who find this valuable and want to contribute to the continued growth, consider becoming either a free or paid subscriber, or even just sharing the article on social media or with a friend. Every bit helps and allows me to justify the effort I put into these each week. If there’s a topic you’d like to see covered here, leave it in the comments below.

Second, I want to highlight a great feature of Substack—the AI audio transcription tool. This feature converts all my posts into audio format so they can be listened to like a podcast. Important note: you can only listen to the audio using the Substack app, so if you haven’t downloaded it on your smartphone and enjoy Substack, I’d strongly suggest it. This has been an absolute game-changer for me. I used to listen to podcasts while working out or commuting, but now I often find myself tuning into posts from my favorite authors on the Substack app.

Housekeeping done!

This week, we have interesting developments in a diverse range of areas in biotechnology:

A scientist took her cancer treatment into her own hands with viruses she grew in the lab - she’s now cancer-free

Illegal Cloning Scheme in Montana Leads to Hybrid Sheep Trafficking and Wildlife Concerns

CRISPR Gene editing can boost sweetness in large tomatoes, but will consumers have a taste for these genetically modified fruits?

A Genomic Foundation Model for Predicting and Generating Complex Biological Sequence

A scientist took her cancer treatment into her own hands with viruses she grew in the lab - she’s now cancer-free

Western movies are one of my favorite genres. Think of classic films like No Country for Old Men, Django Unchained, The Revenant, and Man on Fire. These films, which stem from the traditional premise of Westerns set in the American frontier, embody the struggle and resilient spirit of early pioneers. In these stories, people are isolated, forced to rely on each other in a landscape devoid of institutions and civilization. When something goes wrong or conflict arises, there’s often no legal system, and people are forced to take the law into their own hands.

What does this have to do with biotech? Well, from time to time, we hear about scientists or physicians taking medicine into their own hands after they, or a loved one, fall ill with a deadly disease. I would argue that they, too, are embodying the Western spirit. In fact, there are famous real-life stories that mirror this. One that comes to mind is Lorenzo’s Oil, a movie based on the true story of parents whose son was diagnosed with a rare, fatal degenerative disease. Told there was no cure, the parents refused to accept this and became experts in biology, ultimately finding a treatment to save their son. In many ways, the Western theme can live on the frontier of medicine.

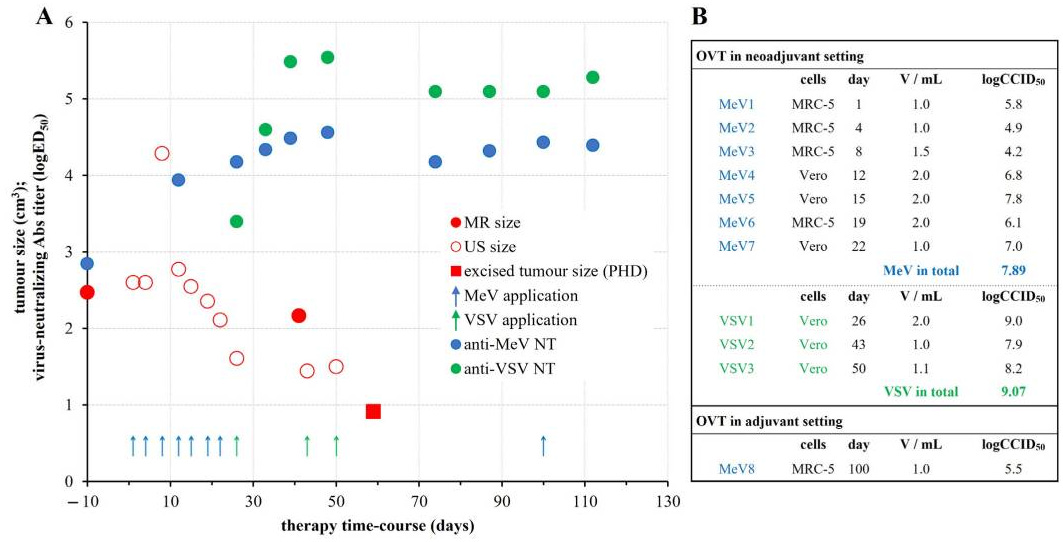

All of this sets the stage for a case I read about recently. Beata Halassy, a virologist at the University of Zagreb, gained attention for treating her own recurrent breast cancer using viruses she grew in her lab (Corbyn, 2024). After the cancer returned for the second time, Beata, who had initially sought treatment from traditional medical institutions, decided to forgo chemotherapy. Instead, she self-administered oncolytic virotherapy (OVT), a novel cancer treatment that uses viruses to destroy cancer cells and stimulate the immune system. Halassy chose two viruses—measles (MeV) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)—known to infect cells similar to those in her tumor. She directly administered the viruses into the tumor site in an effort to reduce its size before opting for surgery.

The OVT led to significant tumor shrinkage, with Halassy's tumor softening and detaching from surrounding tissue, making it easier for surgeons to remove. Histological analysis of the excised tumor revealed a substantial immune response, with increased infiltration of immune cells such as B cells, T cells, and macrophages. All of this, Halassy would later publish in a research article (Forcic et al., 2024).

Despite the success of the self-administered treatment, Halassy’s case has sparked ethical debates, as self-experimentation is fraught with risks. Her oncologists monitored her condition throughout the process, agreeing to intervene if complications arose. This case, though unorthodox, adds to growing interest in OVT as a potential adjunct or alternative to conventional cancer treatments, particularly for patients with difficult-to-treat tumors.

Personally, I find Beata’s relentless pursuit of a cure truly inspirational—she deserves her own movie. But it's worth mentioning that this remains an isolated experiment, even with her encouraging results. To understand the full potential of OVTs as an adjunct treatment, robust clinical studies are essential. Regardless, Halassy’s journey has prompted further investigation into using OVTs as a neoadjuvant therapy to prepare tumors for surgery, showing that virotherapy may stimulate both direct tumor destruction and immune system activation.

Illegal Cloning Scheme in Montana Leads to Hybrid Sheep Trafficking and Wildlife Concerns

In a bizarre wildlife trafficking case, Montana resident Arthur Schubarth was sentenced to prison for cloning a near-threatened Marco Polo argali sheep and trafficking its hybrid offspring for big game hunting. Schubarth illegally imported body parts from the endangered species in Kyrgyzstan and sent this genetic material to a lab to create cloned embryos. These embryos were then implanted into ewes on Schubarth's ranch, resulting in the birth of Montana Mountain King (MMK), a cloned male sheep. MMK’s semen was later used to impregnate other ewes, leading to the creation of hybrid sheep that were sold to hunters (DoJ details).

As the case unfolds, it remains unclear how many of MMK’s hybrid descendants are still at large, raising concerns about their potential to outcompete native sheep species in the US and disrupt local ecosystems. Legal documents reveal that Schubarth sold dozens of MMK’s offspring to individuals across the country. While MMK himself has been accounted for and is now housed at the Rosamond Gifford Zoo in Syracuse, New York, the fate of his hybrid descendants remains uncertain, with some possibly still in private hands.

The case raises important questions about the intersection of cloning technology, wildlife conservation, and international law. Cloning companies are now being urged to exercise greater diligence to avoid becoming involved in illegal wildlife trafficking.

CRISPR Gene editing can boost sweetness in large tomatoes, but will consumers have a taste for these genetically modified fruits?

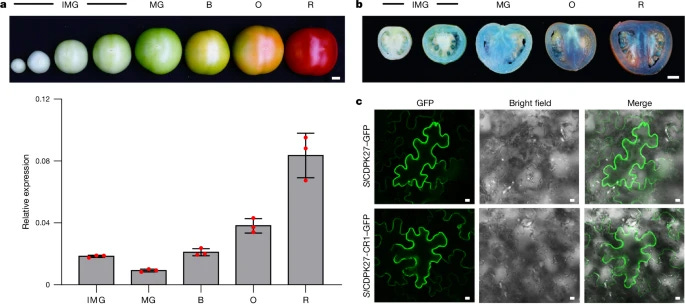

Tomatoes are an essential crop worldwide, but a long-standing issue in tomato breeding has been balancing fruit sweetness with size and yield. Typically, larger tomatoes tend to have lower sugar content, creating a trade-off between taste and agricultural productivity. This dilemma has sparked ongoing research into the genetic mechanisms that control sugar accumulation in tomatoes. Recent studies have shed light on a promising solution to this problem, thanks to the discovery of two genes—SlCDPK27 and SlCDPK26—that act as "sugar brakes" in tomatoes. These genes regulate the degradation of sucrose synthase, a key enzyme in sugar metabolism, through phosphorylation.

In an innovative move, researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to knockout these genes in tomatoes, resulting in a remarkable increase in glucose and fructose levels—up to 30% (Zhang et al., 2024). Notably, this enhancement in sugar content came without sacrificing fruit size or yield, making it a potential game-changer for both consumers and farmers. The edited tomatoes not only scored higher in sugar content but also performed well in taste tests, indicating that the sweetness increase was not just biochemical but also perceptible to the human palate. These findings suggest that we can engineer tomatoes that are sweeter and more commercially viable, without any trade-offs in size or agricultural productivity, pushing the boundaries of what genetic editing can achieve in crop improvement.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have already become an invisible part of our diet. From the soybeans in our processed foods to the corn in livestock feed, GMOs are deeply embedded in modern agriculture. As CRISPR technology advances and our understanding of plant genomes grows, there will likely be increased pressure to genetically manipulate the foods we consume, with promises of higher yields, improved resistance to pests, and longer shelf lives. However, the real question may not be whether these modifications are possible, but whether the public will accept them.

In the U.S., skepticism surrounding GMOs remains pervasive. Many Americans are increasingly aware of the health risks posed by the synthetic chemicals and contaminants that have infiltrated the food supply. The Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement has highlighted the stark contrast between American food products and their counterparts in other countries, where many of the chemicals and additives commonly used in the U.S. are banned. This growing health awareness is likely to fuel further skepticism toward additional genetic modifications of our food and could trigger a significant backlash. Given these concerns, it is critical that any future developments in genetically modified foods be pursued with full transparency and rigorous safety testing to ensure public trust.

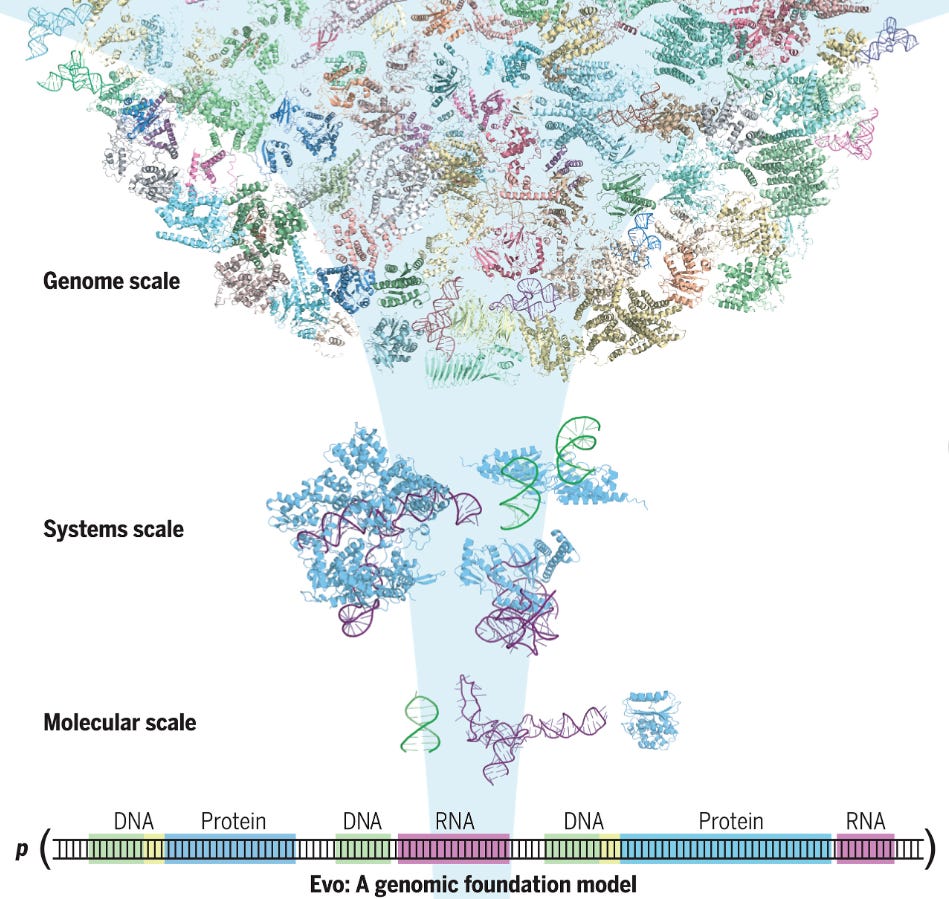

Evo: A Genomic Foundation Model for Predicting and Generating Complex Biological Sequences

At the core of all life is the central dogma of biology, a process that describes how genetic information flows from DNA to RNA and ultimately to proteins. DNA contains the blueprint for an organism’s biology, which is transcribed into RNA, serving as a messenger that carries the genetic instructions to the cell's machinery. This machinery then uses the instructions in RNA to produce proteins, the functional molecules that carry out almost every biological task, from cell division to immune response. However, the genome is enormous and understanding exactly what each gene does, how genes work together, and how genetic changes affect the organism is one of the greatest challenges in modern biology.

The complexity of this process lies in the fact that genes don't operate in isolation—they interact with other genes, regulatory factors, and environmental influences in intricate ways. Predicting how one gene's activity will influence another, or how mutations in a gene will impact the whole system, is a monumental task. Traditional methods of studying genes involve piecing together data from real-world studies that knockout a gene and look for an associated effect. This data then feeds specialized models, each one focused on a narrow aspect of biology—such as protein function, gene regulation, or mutation effects. This fragmented approach makes it difficult to obtain a unified understanding of how genes interact in the context of the entire genome. The challenge is even greater when considering the vast amount of data available today, requiring tools that can process and analyze this information on a genomic scale.

If you’ve been reading about AI, you can probably see where this is going. Scientists have attempted to solve this big data and prediction model by building an AI model named Evo. Evo is a machine learning-based model that can handle multiple genetic tasks in one system, such as predicting gene functions, understanding how genes interact, and even generating new genetic sequences (Nguyen et al., 2024). By analyzing vast datasets—such as the genetic information of millions of organisms—Evo makes predictions about how genes will behave in different contexts, without needing task-specific models for each task. Unlike traditional models that focus on one aspect of biology at a time, Evo’s strength lies in its ability to generalize across multiple tasks, enabling it to predict gene functions, the effects of mutations, and how genes work together, all in one go. Its ability to make zero-shot predictions—making accurate predictions about genes it hasn’t been explicitly trained on—makes it a game-changer. Evo not only helps scientists better understand the biology of genes, but also opens new possibilities for synthetic biology, genetic engineering, and precision medicine by providing an efficient, scalable, and integrated tool for decoding the genome.

One of the most promising applications of Evo is its ability to predict gene essentiality, or genes critical for survival and growth of an organism, in bacteria and bacteriophages at the genome scale. This is particularly significant in the fight against antibiotic resistance. By identifying which genes are crucial for the survival of pathogens, Evo opens the door to new therapeutic targets, potentially accelerating the development of novel antibiotics and other treatments. Evo’s zero-shot prediction capability allows researchers to make these predictions across diverse organisms without relying on detailed annotations, making it a powerful tool for both basic research and practical drug development. As antibiotic resistance continues to rise, Evo’s ability to streamline the identification of essential genes offers a critical step forward in the battle to combat resistant infections.

Support:

These newsletters take a significant amount of effort to put together and are totally for the benefit of the reader. If you find these explorations valuable, there are multiple ways to show your support:

Engage: Like or comment on posts to join the conversation.

Subscribe: Never miss an update by subscribing to the Substack.

Share: Help spread the word by sharing posts with friends directly or on social media.

References:

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/montana-man-sentenced-federal-wildlife-trafficking-charges-part-yearslong-effort-create

Corbyn, Zoe. "This scientist treated her own cancer with viruses she grew in the lab." Nature.

Forčić, D., Mršić, K., Perić-Balja, M., Kurtović, T., Ramić, S., Silovski, T., Pedišić, I., Milas, I. and Halassy, B., 2024. An Unconventional Case Study of Neoadjuvant Oncolytic Virotherapy for Recurrent Breast Cancer. Vaccines, 12(9), p.958.

Nguyen, E., Poli, M., Durrant, M.G., Kang, B., Katrekar, D., Li, D.B., Bartie, L.J., Thomas, A.W., King, S.H., Brixi, G. and Sullivan, J., 2024. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science, 386(6723), p.eado9336.

Zhang, J., Lyu, H., Chen, J., Cao, X., Du, R., Ma, L., Wang, N., Zhu, Z., Rao, J., Wang, J. and Zhong, K., 2024. Releasing a sugar brake generates sweeter tomato without yield penalty. Nature, pp.1-10.

Fantastic work, David. Look at that growth!! Amazing.

Sadly, I've been at a plateau for what seems like months now. Strange, but oh well.

Anyway, great round-up, as ever. You're exceeding Nature Briefings in these. ;)

The application of AI to structure/function prediction and modelling is getting very impressive.

Good post!