BioWire Bytes 017 – A Glimpse of How Embryos Burrow into the Womb

Byte-sized biotech

The development of a freshly fertilized single-cell embryo to a fully matured organism has to be the single most fascinating and mysterious feat of biology. It’s nothing short of incredible that this first single cell contains the instructions to create a full organism, and it reliably happens the same way every time for each animal, including humans. It’s like watching magic happen. Perhaps you or someone you know has gone to an IVF (in vitro fertilization) clinic to utilize assisted reproduction technologies. The couple had oocytes (egg cells) extracted from the female partner, which are fertilized and grown to blastocysts, the stage at which embryos implant into the uterine wall. Even this process is a marvel to watch (see the video below).

Surprisingly, it turns out the implantation process is far from gentle. For the first time, scientists have captured up-close footage of a human embryo implanting into a uterus-like environment, and it does this with surprising force (Godeau et al., 2025). In this normally hidden moment usually tucked away in the womb, a tiny cluster of cells just a few days old behaves more like a determined tunneler than a delicate passenger. While perhaps not a biotech breakthrough, its an incredible event to watch unfold and illuminates how an embryo physically burrows and reshapes their surroundings to nestle into the uterine lining. With this implantation period among the most critical and failure-prone, researchers are opening fresh avenues to understand and perhaps overcome one of fertility’s biggest hurdles.

First, if you enjoy these updates, consider subscribing and becoming a part of our growing community!

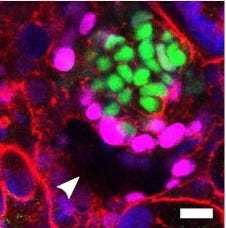

An interesting new study used a synthetic uterine model, essentially a lab-grown tissue of the uterine lining, to observe implantation. To do this, researchers placed human embryos onto a gel matrix rich in collagen, the key structural fibrous protein that makes up much of the uterine tissue. Then, using time-lapse microscopy (a frame every 20 minutes over about a day), they watched the implantation process unfold.

What did they see?

The blastocyst, which at this stage is about the size of a poppy seed, latched on and quickly plunged inward, pulling the gel’s fibers around itself as it buried deeper and deeper. One scientist admitted her first reaction was to suspect a microscope error – surely the embryo couldn’t be moving that fast on its own! But it was. The embryo literally yanked its environment apart to make itself at home. This goes beyond the long-known chemical side of implantation (embryos do secrete enzymes to soften up the uterine tissue). The footage makes clear that chemistry isn’t enough, the human embryo also works like a mechanical miner, actively wriggling and pushing its way into the uterine wall with physical force. In essence, it remodels its new home rather than just sidling in.

How does this compare to embryos from other species?

Equally fascinating is what happens in other species. The researchers performed the same experiment with mouse embryos, and the difference was dramatic. Mouse embryos don’t burrow like their human counterparts; instead, they spread out on the surface of the uterine lining. Imagine the mouse embryo as a plant that grows and expanding across a surface, whereas the human embryo is digging and embedding itself directly into the soil. The mouse trophoblast cells (the embryo’s outer layer) tended to crawl outward in a flatter sheet. In utero (real pregnancies), a mouse embryo triggers the uterus to fold around it, nestling the embryo in a little uterine crypt. But a human embryo dives right in on its own, embedding completely inside the uterine wall. This species-specific events underscores that there’s no one “universal” way embryos implant, each species has evolved its own approach. Humans, with their highly invasive placentas, begin the invasion early and aggressively, while mice take a somewhat gentler approach on the surface. These differences aren’t just academic; they hint that mechanical implantation strategies co-evolved with pregnancy styles, and studying them side-by-side helps pinpoint what truly matters for success in each case. Perhaps this even gives clues as to why human embryos implant in areas they aren’t suppose to as in ectopic pregnancies, while this is unheard of in most other mammals.

So, Is it the seed or the soil?

Digging deeper (literally), the researchers measured the mechanical forces at play. By tracking how the collagen fibers moved, they could map the traction “footprint” of the implanting embryo. The human embryo generated a web of tiny tugs in all directions – multiple traction points that it used to pull itself in. You can picture the embryo like a little rock climber, throwing out several grappling hooks into the surrounding tissue to haul itself forward. In contrast, the mouse embryo’s pulls were concentrated along just a couple of main axes, aligning with its flattened spread. These mechanical maps were not just visually striking; they carried biological significance. In both animals, strong and dynamic pulling correlated with successful implantation. Embryos that pulled weakly or erratically were often the ones that failed to properly embed. In fact, the study noted that “implantation-impaired” human embryos exerted significantly less force on their matrix. It appears that an embryo needs a certain physical vigor or literal strength to establish a pregnancy. This finding sheds new light on why implantation is such a notorious bottleneck in fertility (accounting for roughly 60% of miscarriages). It’s not simply about the embryo’s genetics or the hormones in the uterus; the physics of the embryo’s push matters too. Perhaps there may be a future where fertility assessments measure an embryo’s ability to generate mechanical forces, or perhaps treatments to help an embryo that isn’t gripping well enough.

Even more intriguing, the embryo seems to “listen” to its environment as much as it talks. When the scientists gently tugged the matrix with a tiny tool, the embryo sensed the external force and redirected itself toward it, establishing what the team dubbed a “mechanical bridge”. In natural conditions, this might mean that uterine micro-contractions or firmer spots in the tissue guide the embryo toward the richest blood supply – essentially helping the embryo orient to where the nutrients are. It’s amazing to think of this microscopic ball of cells is being guided by such subtle signals. Life’s very beginnings involve a two-way handshake: the embryo pulls and the uterus, in its own subtle ways, pulls back.

Okay, these are visually stunning observations. But what’s the impact?

The most obvious thing that comes to mind here are some ways that this information could be the predicate for technology that improves IVF embryo selection and even provide fertility treatments. But there are some other interesting applications, and one you may be thinking of: the emerging quest to build artificial wombs. We’re in an era of audacious bioengineering, researchers and startups around the world are imagining how we might sustain pregnancies outside the body. The new findings may indicate a crucial fact: an artificial uterus will need to do more than provide nutrients and hormones; it must also replicate the physical cues and perhaps even the gentle motions of a real uterus. In other words, a future “bio-incubator” has to be not just a life-support device, but a mechanical partner to the embryo.

These newsletters take significant effort to put together and are totally for the reader's benefit. If you find these explorations valuable, there are multiple ways to show your support:

Engage: Like or comment on posts to join the conversation.

Subscribe: Never miss an update by subscribing to the Substack.

Share: Help spread the word by sharing posts with friends directly or on social media.

References:

Godeau, A.L., Seriola, A., Tchaicheeyan, O., Casals, M., Denkova, D., Aroca, E., Massafret, O., Parra, A., Demestre, M., Ferrer-Vaquer, A. and Goren, S., 2025. Traction force and mechanosensitivity mediate species-specific implantation patterns in human and mouse embryos. Science Advances, 11(33), p.eadr5199.

Absolutely marvelous explanation and topic. Thank you so much for sharing!!!